But I'd made at least ten telephone calls every day since then, from Brighton to Birmingham and back to London, without ever once getting through to that inimitable, halting voice. A month of pleading with agents and publicity officers, all of whom sounded terrified at the very thought that I should claim a whole hour of Miss Dietrich's time to myself.

By then my mental picture of her was becoming a little unsure. Perhaps that brief meeting among a horde of people in the excitement of a first arrival had been misleading. Perhaps the apparent ease and friendliness of the magic Marlene was just an effect, switched on like her magnificent stage personality, for an audience which expected it.

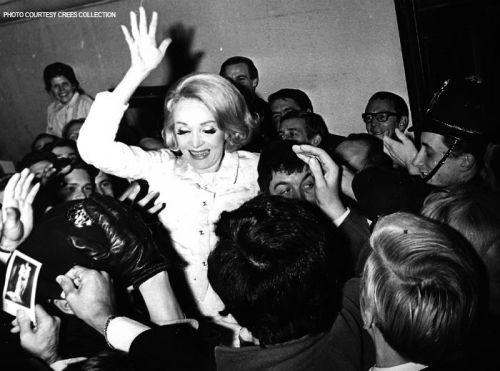

Police cordons

.jpg) In between times I'd heard of the packed schedule of a tour which stopped in each city for only a week, which included intense rehearsals with each orchestra, with her arranger Burt Bacharach (who flew from the U.S.A. especially), an entire one-woman radio play for the BBC somehow jammed into the London week; of fantastic hold-ups every night after each show while fans besieged the stage doors so that Dietrich could not emerge without special police cordons.

In between times I'd heard of the packed schedule of a tour which stopped in each city for only a week, which included intense rehearsals with each orchestra, with her arranger Burt Bacharach (who flew from the U.S.A. especially), an entire one-woman radio play for the BBC somehow jammed into the London week; of fantastic hold-ups every night after each show while fans besieged the stage doors so that Dietrich could not emerge without special police cordons.

Perhaps I was hoping for too much. Then I got word that she was fed up with English reporters asking about nothing but her age, her looks, her clothes, and that most forbidden of all subjects, her family – about whom she will never speak.

All the signs were against my ever getting to see her at all. Yet, throughout I had a curious belief that it would come off – because of the geranium.

Miss Dietrich had, that first night, told an endearing story: ''I've just made a new LP. The songs of old Berlin as I remember them as a child. They are beautiful songs, real songs of the people. And because they always meant so much to me, I wanted to do everything about this record myself. Even to designing the cover. Me, I'm not an artist. But I had my ideas. I always see Berlin as a grey city – grey walls, streets, everything.

"So I got paints and made a beautiful grey pattern. Then, because I'm not an artist, I went to a stationer's and bought those letters children use to scratch with a pencil and that come out on paper.

"Then on the bar of the 'H' at the end of my name I put a lovely little pot of bright red geraniums. When I took it proudly to the publisher, he said, 'Why the geraniums there?' I tried to explain that it is the flag of the little people in grey cities everywhere. The big gesture of the bourgeois toward beauty. And I am a bourgeois and I love geraniums.

"But, of course, he couldn't understand. Never mind, I kept my geranium on the cover – just as I always keep one in my dressing-room wherever I go."

And sure enough, when finally, after many cancellations, I got to her dressing room at Golder's Green Hippodrome on the outskirts of London, there it was. Not a grand florist's specimen,but a simple little scarlet single in a common terracotta pot sitting on the wash basin in the corner.

Beside it on the wall was a symbol of that very private side of Dietrich's life she seldom mentions, a

large framed and inscribed portrait of Ernest Hemingway, wearing a polo-necked sweater and looking young and adventurous.

On a previous occasion I had once managed to get her to touch on her great friend ship with this man who wrote of her: "I think she knows more about love than anyone. I know that every time I have seen Marlene Dietrich she has done some thing to my heart and made me happy.''

It was when she was railing against the agonies of work on tour: "It is not the performances I mind. They are fine. Once I am in front of people I can recharge my batteries from them.

''It is the terrible chore of packing and unpacking. Of never having a minute to myself or a second for reading."

Then someone asked who was her favourite author and, suddenly, the whole face softened and glowed. She replied with the single word, "Hemingway."

She began to speak of the great respect and love she felt for him; her voice broke, she turned away with a final, "Life is not the same now he has gone."

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+-+from+lastgoddess.blogspot.com.jpg.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)