Pages

04 December 2014

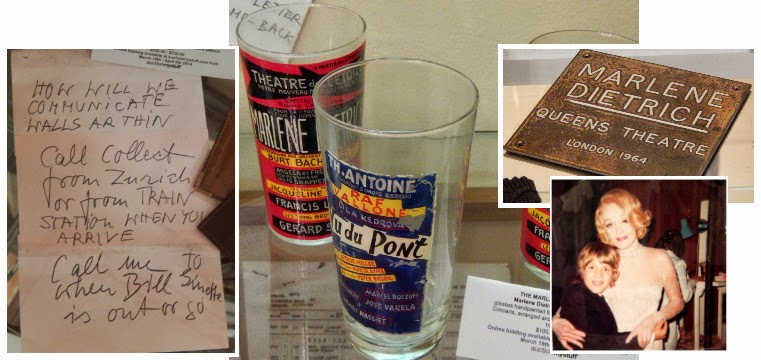

Pretty Souvenirs: A 2014 Marlene Dietrich Auction Overview

10 January 2014

Jean Marais reads Jean Cocteau's Salutation to Marlene Dietrich (1954) [...

Jean Marais reads Jean Cocteau's Salutation to Marlene Dietrich, written in 1954 when Marlene appeared in Monte Carlo for a Polio benefit. (The recording, and Marlene's speech at the end, were likely done later).

Photos show Marlene at the benefit performance in Monaco, in Paris and London; with Marais and Cocteau (between 1954 - 1959); receiving the Legion d'honneur (1951); and at the 10th anniversary of the liberation of Paris.

TRANSLATION:

Marlene Dietrich! ... Your name, at first the sound of a caress, becomes the crack of a whip. When you wear feathers, and furs, and plumes, you wear them as the birds and animals wear them, as though they belong to your body.

In your voice we hear the voice of the Lorelei: in your look, the Lorelei turns to us. But the Lorelei was a danger, to be feared. You are not: because the secret of your beauty lies in the care of your loving kindness of the heart. This care of heart is what holds you higher than elegance, fashion or style, higher even than your fame, your courage, your bearing, your films, your songs.

Your beauty is its own poet, its own praise. There is no need for us to speak of it, and so I salute, not your beauty but your goodness. It shines in you, as light shines in the moving wave of the sea: a transparent wave coming out of the far distance, and carrying like a gift, its light, its voice, and the plumes of foam, to the shore where we stand.

From the sequins of the "Blue Angel" to the dinner-jacket of "Morocco", from the shabby black dress of "Dishonored" to the cockfeathers of "Shanghai Express": for the diamonds of "Desire" to the American uniform: from port to port, from reef to reef, from crest to crest, from breakwater to breakwater, there comes to us (all sails flying) a frigate, figurehead, a Chinese fish, a lyre-bird, a legend, a wonder: Marlene Dietrich!

(Translated by Christoper Fry)

Written as introduction for Miss Dietrich's appearance at the French Polio Benefit in Monte Carlo (Monaco

02 September 2012

Marlene '59

|

| Marlene Dietrich at the Sahara Hotel, 1959. |

She sang her usual suspects but included an odd repertoire choice: Johnny Cash's "Don't Take Your Gun To Town".

In 1959, Marlene also announced her TV debut. Press were told that her upcoming performances in Paris would be filmed in colour, directed by Orson Welles. In the end, the special -- a French-language performance filmed for an American TV audience -- didn't happen, but Marlene did make her TV debut that year, without fuss, while on tour in Brazil.

|

| Marlene makes her TV debut on Brazil's TV Tupi. With host, Jayce Campos (1959). |

08 August 2012

When Baryshnikov & Dietrich Met on Business

Absent from the ceremony was Marlene Dietrich, who had won a lifetime achievement award, which someone less respectful than I might term a sort of "deathbed award" that Dietrich describes under her ABC entry, "Academy Award." On Marlene's behalf, Mikhail Baryshnikov accepted the award. Maria Riva tells us in her book that Dietrich rejected David Riva for this task in favor of the diminutive dancer-turned-actor, who became the object of her mother's unbridled octogenarian lust.

If Baryshnikov never had the chance to visit Dietrich's "nice and tight" nether regions, at least one of her top-shelf impersonators, played by Adele Anderson, flirted with him and Gene Hackman in the 1991 movie, Company Business. This Dietrich may be dressed like The Blue Angel's Lola-Lola, but she's singing "The Boys in the Backroom," the signature song of Destry Rides Again's Frenchy, even jiggling her Adam's apple like the saloon strumpet to whimper with vibrato!

11 July 2011

Derek Prouse Interviews Marlene Dietrich: "I Hated Being A Film Star" (1964)

What clues does the flat in the elegant Avenue Montaigne afford to the character of its celebrated occupant?

An uncountable mould of suit cases in the hall; a salon impersonally furnished, the décor of a constant traveller, a purposeful book case whose books are clearly there to be read: Goethe, Scott Fitzgerald, the collected scripts of Ingmar Bergman; a large photograph of General de Gaulle inscribed: “Pour Madame Dietrich – en temoinage d’admiration pou son magnifique talent.”

Dietrich enters: one feels instantly that here is a shy and private woman; the flowers one has brought to her she holds almost defensively before her face; this is a subtle way of saying “thank you” without words. She places them attentively in a large vase on a desk, and it capriciously keels over. Suddenly we are under the desk in a spreading pool of water and spiteful rose stalks. The ice is broken.

Out of the busy coming and going of the mopping-up operation a few random phrases are speared: “I’m not a myth” . . . “I never see the Press … why should I?” . . . “America? A country can stay young for too long. Everything that is new is still automatically the best there” . . . “The thirties? Who wants to hear about old films nowadays?”

“I do,” one asserts. Obviously, sooner or later we must speak of The Blue Angel and the man whose name was inseparably linked with hers for so long, Josef von Sternberg.

“Well, Mr von Sternberg came to the theatre to see some actors he wanted for The Blue Angel and I happened to be in the play. That was towards the end of ’29. I was at the Max Reinhardt theatre school in Berlin. (There’s not much done in the theatre today, and called new, that Reinhardt didn’t do first.)

“Reinhardt had four theatres in Berlin and in the evenings we students would have to go around saying ‘The horses are saddled’ in the first act of this play or ‘Here’s a letter for you, Madam’ in the third act of another – as part of our training.

“After the success of The Blue Angel I just went with Mr von Sternberg to America for one film. One film – and then if I didn’t like the place I would be allowed to leave. Otherwise I wouldn’t have gone; I wanted no seven-year contract or anything like that. I had to look at the country first; I didn’t know if it was good enough for my child. Then I saw it was good and brought her over and my husband came whenever he could; he was working here in Paris for Paramount. But then Hitler came in and we got stuck in America. The film I liked best? The one that had the least success: The Devil is a Woman.

“And after you left von Sternberg?”

“I didn’t leave Sternberg (the faintly weary voice suddenly rises in passionate assertation; the only time the deferential “Mr” is forgotten). “He left me! That’s very important. In my life he was the man I wanted to please the most. He decided not to work with my any more and I was very unhappy about that, before that, Mr von Sternberg had picked Rouben Mamoulian to direct Song of Songs and I love Mamoulian because of his kindness to me at that time. It was the first time I’d worked without Mr von Sternberg and I behaved atrociously. I thought I’d never do anything again since he left me.

“Perhaps I’m wrong to say I was unhappy – you can’t be made really unhappy by something you’re not interested in. My heart was never in that work. I had no desire to be a film actress, to always play somebody else, to be always beautiful with somebody constantly straightening out your every eye-lash. It was always a big bother to me. And I hated the stupid publicity that was created around one.”

“Like that much publicised feud with Mae West, for instance?”

“Not at all true. She was very kind to me. And she’s such a witty woman.”

The voice was becoming low, almost distant. “No. It’s so difficult playing somebody else. I like playing myself.”

“Is that way you prefer working in cabaret?”

Dietrich’s long career has not been without its perilous impasses; at the end of her association with von Sternberg her stock was dangerously low in Hollywood. With Desire, that witty film directed by Frank Borzage in which she played an international jewel thief, she swept back into favour.

But it was at Universal that she made one of the greatest and most unpredictable successes: In Destry Rides Again, gone were all the glamorous trappings; the atmosphere of aloof, impregnable mystery that had always been her stock-in-trade was exploded. Instead, a brawling saloon-entertainer in the West, dodging guns and belting out “See what the boys in the backroom will have.” Was this transformation Dietrich’s own idea?

“No it was Joe Pasternak’s. He made the decision.”

“And you were in favour of it?”

“I needed the money.” Flat factual and forthright, this statement imposes a pause.

“But you must have enjoyed it.”

“No! (a protesting cry.) I – never – enjoyed – working – in – a – film. You have to get up at the crack of dawn, and then you have to get prettied up all day long and every hair has to match the next day and 60 000 people fool around with you. It is just awful. Anyone who enjoys that … (the voice trails away in speechless stupefaction).

“But I was grateful for one thing: the big legend that the Paramount publicity machine built up did, paradoxically, afford me privacy. I never like to talk about myself: I think that no one has a right to know about one’s private life and private affairs. Mr von Sternberg said: you have to give the magazines something to print so the glamorous legend was fine, even if there wasn’t a word of truth in it.” (The “legend” that was exhaustively “plugged” during the thirties implied that Dietrich was a Trilby manipulated by von Sternberg, her dark and mysterious Svengali.”

“But now I do the work I enjoy. I’ve toured South America. I’ve played all the Scandinavian countries, Russia, Israel, Holland and many others.

“But you always come back to Paris?”

“Everybody loves Paris – even Hitler didn’t dare to push the button. And Paris has always recognised artists; it understood von Sternberg and it understands Orson Welles. When I talk with him I feel like a plant that has been watered.

“And in Paris there is freedom: they let you live and nobody bothers you. You can do what you want, live with whom you want, and that’s wonderful – no? They are so full of their own lives that they have no time to bother about anybody else’s. I can go to the meat man and buy my meant and nobody pesters me. They say ‘Bonjour Madame Marlene’ and pass me by.”

Dietrich moves out on to the balcony. The Avenue looks bleak and anonymous but to her seems beautiful. “They’ve cut down my trees,” she murmurs wistfully. Chekov has taken over. But the telephone soon snaps her back to her intense professional world.

“I’ve just made a new record. I produced it myself. Fifteen songs of Berlin; songs of the town in the old days. Berlin always had something special; it was always in island. An island with its special kind of tragic wit without self-pity and without reverence.”

I recall Johnny, which Dietrich first recorded in 1929 and which is in her recent long-player. She sings in German:

Johnny, when you have a birthday

Come and be my guest

For the night.

The singer, the song and the invitation seem to have gained with the years. The spell is potent and not easily broken.

I left, remembering Jean Cocteau, who told me just before his death that he had arranged to hire a copy of Shanghai Express (one of Dietrich’s early Hollywood successes). “I wanted so much to see ‘chere Marlene’ once more,” he said.

One sees what he meant: a legend can often boomerang, but Dietrich, by hard work and artistry, has kept hers meaningful and alive.