This entry is part of the 2012 Queer Film Blogathon, co-hosted by Garbo Laughs and Pussy Goes Grrr. While you're here, please read my contribution to the 2011 Queer Film Blogathon, Throwing Shade: Homophobia in Riva's Dietrich Bio? Pt. 1. You can also browse our entries tagged "LGBT."

Now that summer's upon us, I'd like to make a proposal that none of you should refuse. Instead of trekking across Yosemite, spelunking in Carlsbad Caverns, or zip-lining through the Redwoods, consider roughing it in my camp. There's just one caveat. I've assigned some required reading. Don't worry. You've probably already read this text in an introductory film course, an introductory queer studies course, or an introductory queer film studies course. If none of those apply to you, maybe you've read it elsewhere--

Susan Sontag's seminal work,

"Notes on 'Camp.'" In case I've offended any of you radical separatist feminists, you ought to leave now because this blog is like a can of Vienna sausages--not that I'm pushing my patriarchal power on you or anything--no, siree! For you less radical or non-separatist feminists, please forgive my male privilege and substitute "ovular" for "seminal." As for you trans-folk, I can never do right by you, so rip me a new one in the comments section.

In "Notes on 'Camp,'"

Marlene Dietrich scores Note No. 25 with

Josef von Sternberg, which I find eerie because, you know, two plus five makes seven--the number of films that the two made together. Maybe Sontag consulted

Carroll Righter before arranging this list, or maybe I've been drinking too much

go-go juice. Let's eschew that balderdash and delve into what Sontag in fact says regarding Dietrich and Sternberg: "Camp is the outrageous aestheticism of Sternberg's six American movies with Dietrich, all six, but especially the last,

The Devil Is a Woman. . . ." Just to clarify, the five other films that Sontag doesn't name are

Morocco,

Dishonored,

Shanghai Express,

Blonde Venus, and

The Scarlet Empress. Now, what could Sontag have possibly meant by "outrageous aestheticism"?

|

| Is it high heels in the desert sand?

|

|

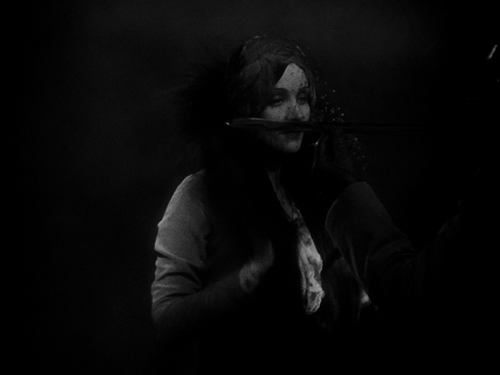

| Is it primping for one's execution with a soldier's sword as a mirror?

|

|

| Coincidentally, Sontag declares in Note 25 that "Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers."

|

|

| Perhaps outrageous aestheticism is making vagrancy look fabulous. In the 21st century, the Olsen twins would wear this look to the Met Gala, and the media would call it "boho chic."

|

|

| Could it be horses galloping up staircases?

|

|

| How about smoking a cigarette while rolling them as a factory worker? |

Of course, the more obvious examples of "outrageous aestheticism" would include a beautiful woman emerging from

a gorilla suit or wearing

a top hat and tails. If outrageous aestheticism is about an excessive or extravagant emphasis on appearances, then I agree with Sontag's assessment. My view of camp, however, diverges from Sontag's because of the opposition that she describes in Note 51: "The two pioneering forces of modern sensibility are Jewish moral seriousness and homosexual aestheticism and irony." Long before I even knew of "Notes on 'Camp,'"

James Naremore had already examined notes 25 and 51 together, accepting Sontag's dichotomy of sensibilities with the assertion that Sontag associates Sternberg with "homosexual aestheticism and irony."

Cut! Sternberg wasn't gay, but he was a Jew. In fact, I often neglect the coded antisemitism in comparisons of Sternberg to

Svengali, that famous literary character from

George du Maurier's

Trilby whom

Edgar Rosenberg analyzes in his often-cited text,

From Shylock to Svengali: Jewish Stereotypes in English Fiction. What are we to make of this situation? Is Sontag mistaken to attach sensibilities to particular minorities when we can regard Sternberg as a Jew whose work exemplifies camp? Not necessarily. One need not be a member of a group to make movies in its style, which is evident in the non-black filmmaker

Jack Hill's blaxploitation films,

Coffy and

Foxy Brown.

Although I can reconcile the straight, Jewish Sternberg's intensely personal (a word I use here in its proprietary sense) aesthetic--which screams, "Camp!"--with the idea of camp as a predominantly gay men's style, I have to ruminate on the ground rules established by Sontag regarding who can delineate a sensibility:

For no one who wholeheartedly shares in a given sensibility can analyze

it; he can only, whatever his intention, exhibit it. To name a

sensibility, to draw its contours and to recount its history, requires a

deep sympathy modified by revulsion.

When I first read this prerequisite, I immediately wanted to dismiss the entire text because it appears to deprive those responsible for propagating a sensibility of the ability to discuss it. Thus, I wanted to cast "Notes on 'Camp'" as a homophobic screed, which the likes of

D.A. Miller have already articulated. In

"Sontag's Urbanity," Miller convincingly characterizes Sontag as a homophobe attempting to wrest camp from gay men, especially taking issue with the Sontag quote above and Sontag's claim that someone else would have invented camp had gay men not done so. After further consideration, I now see Sontag's point, regardless of whether Miller's portrayal of her is accurate.

Indeed, revulsion is the secret ingredient that allows a person to scrutinize a sensibility, and Miller in fact ignores the phenomenon of gay men who express a loathing of camp despite exemplifying it. Such is the paradox of internalized homophobia. I recall that when I was in middle school, I was horrified after hearing myself in a videotaped class presentation. This isn't by any means a uniquely gay men's experience, but it can be and has been a nuanced one for gay men who feel disgusted by the sound of their voice because they deem it camp, queeny, effeminate, or gay. Despite that first and ongoing experience of self-repugnance, I learned that I could also delight in exaggerating my speech to play gay caricatures in various academic, professional, and social situations. Therefore, my actions would fall under the category of deliberate camp, which Sontag contrasts with naive camp in Note 18. Incidentally, my internalized homophobia enables me to laugh at Sternberg's ridiculous images of queer characters, figments of his own homophobic imagination.

|

| "Don't worry. I've got a kid of my own. Good luck." We were supposed to laugh at that, right? |

|

| Some stereotypes go back centuries. Snip! Snip!

|

By acknowledging my internalized homophobia, I can stake my claims as both an analyst and exhibitor of camp sensibility, thus conceding somewhat to Sontag's model. On the other hand, I find myself in a quagmire of a quandary as I try to determine whether camp would have developed without gay men, even if I narrow my focus on Sternberg. The straight Sternberg all but denies his influences in the 1967 BBC documentary,

The World of Josef von Sternberg, which almost misleads me into believing that Sternberg could have conceived his camp sensibility himself. Maybe the BBC interviewer

Kevin Brownlow fails to extricate a neat list of influences because Sternberg has already cited them in his 1965 memoirs,

Fun in a Chinese Laundry.

One influence,

Romaine Fielding, was a straight actor-director who was nonetheless very camp. According to Sternberg, the prodigal Fielding once visited the film lab where Sternberg was working "in an electric cabriolet, footman and all, wearing a black cape and sombrero." Truth be told, Sternberg describes Fielding with homoerotic adoration, recalling that Fielding used his eyes to charm Sternberg into loaning him money, but I admittedly could be reading too much between the lines. Sternberg expounds on other directors who influenced him, some of whom may have been gay (e.g.,

F.W. Murnau and

Mack Sennett).

Rather than chart Sternberg's creative lineage to identify any gay predecessors, I should be acknowledging the gay man who helped create the lavish fashions in his Dietrich movies,

Travis Banton. In her memoirs, Dietrich misnamed him Travis "Benton"--unaware of the embedded slur, I hope. Whether we call him an influence or a collaborator, Banton deserves credit for contributing to the "outrageous aestheticism" described by Sontag, and I don't know how we could possibly say that Sternberg and Dietrich could have created this camp style without Banton. Let's remember the one Dietrich-Sternberg vehicle that Sontag doesn't qualify as camp,

The Blue Angel, which was made in Germany without Banton's creative eye.

Still, I'm left with Sontag's baffling characterization of moral seriousness as Jewish, but if I acquiesce to Sontag's philosophy regarding the analysis of sensibilities, I'd argue that Sontag got seriousness all wrong because she was only capable of exhibiting it. In her astute anti-eulogy,

"Desperately Seeking Susan," Terry Castle explains that Sontag's "carefully cultivated moral seriousness – strenuousness might be a better word – co-existed with a fantastical, Mrs. Jellyby-like absurdity," and the reference to terms Sontag herself used in "Notes on 'Camp'"--"moral seriousness" and, in its grammatical variants, "absurdity"--doesn't escape my attention. By blurring the lines of her own sensibility binary, Sontag appears less understanding of camp than she seems and could be a prime example of naive camp, which may not have been

morally serious but was at the very least--to quote "Notes on 'Camp'"--"dead serious."

As you point out, it's fashionable to denigrate Suz's original essay, and while I often can't disagree with those who point out the problems, I still have a lot of affection for it (and this post makes me want to return to it, since it's been a long time since I last read it, especially since I had never considered the Jewish seriousness/homosexual aestheticism issue).

ReplyDeleteAny theoretical quibbles aside, the images you selected are simply divine!

-jesse

Jesse, it's an essay that I often reread, especially because I can easily find it online here. There are likely typos on that page (e.g., Sternberg is called Steinberg), but at least I don't have to dig around for my copy of Against Interpretation. About Sontag's idea of Jewish moral seriousness in a film context, I've always found it puzzling because so many creative Jews in Hollywood really pushed the envelope in terms of morals (e.g., Billy Wilder). If anything, the moral seriousness against which I'd pit camp aestheticism is that of conservative Christians. Jewish studio heads may have approved the Production Code, but it was Christians who came up with it.

DeleteOh, fundamentalist Christianity is intimately acquainted with camp. One need only look at the arts they make for themselves, be they Jack Chick comics or Ron Ormond's Christploitation movies, to see that. Or just sit through old episodes of the PTL club.

DeleteFor myself? I dunno. The very concept of "camp" has always seemed like a kind of fata morgana to me.

I'll put it out there now! Tammy Faye Bakker exuded more camp in her Lee press-on pinkie than Marlene Dietrich did during her entire career. So did Baby Lu-Lu. I get my kicks from other faiths, too. When I was growing up in the San Diego area, the fabulous and fierce Uriel was proselytizing on public access, and that lady out-camped even Tammy.

DeleteHow funny you'd compare the concept of "camp" to a fata morgana when it appeals to fairies like me so much. Seriously, I think any sensibility is an illusion. Even though I could never take Tammy Faye and Uriel seriously with all their trappings, they must have had faithful followers who watched them earnestly. It's a simple difference of tastes.

One of my favorite moments on the last season of RuPaul's Drag Race was when Sharon Needles quipped that it was Tammy Faye Bakker who inspired him to try makeup as a little boy. :D

DeleteI hadn't taken Sontag's comment on "Jewish moral seriousness" as some kind of inherent quality in all Jewish people, but rather as their long tradition of moral and ethical consideration which culminated in the post-War era with Adorno's famous question "can there be poetry after Auschwitz?" (The word "camp," of course, usually has a very different connotation within a Jewish context). And I can't imagine Sontag was unaware of the equally long tradition of Jewish humor--I imagine that she sensed/located a proto-"camp sensibility" in the frission created between these two extreme impulses of seriousness and humor. It would have helped if she had expanded on the thought a bit more, however!

-jesse

Tammy Faye was an inspiration, and that pink-wigged Jan Crouch has nothing on her!

DeleteI can't disagree about the post-Holocaust sobriety, which was prevalent in the early '60s with the Israeli-Arab tensions and the Nokmim. I found Sontag's characterization rather myopic, but I myself suffer from tunnel vision because I tend to focus more on Jewish humor--from Borscht belt legends like Belle Barth (who surprisingly didn't give birth to Joan Rivers), to vaudeville stars like Sophie Tucker, and obviously to Hollywood heavyweights like the Marx Brothers and Al Jolson. Of course, I recognize that seriousness and humor can be contrapuntal (e.g., the aforementioned Christian examples). Because I mentioned Joan Rivers, I should add that she's quite an amalgamation of camp and moral seriousness, and sometimes what makes her ridiculous is her righteousness.

Although Sontag didn't elaborate, I understand why. "Notes on 'Camp'" is written like it's a grocery list, as if it isn't even meant to be taken seriously. It's a bit camp itself!

I LOVE your photo captions! LOL!!

ReplyDeleteThanks! They came as an afterthought, but I think it's necessary to have something playful to contrast with the pseudo-academic rambling.

DeleteThank you for such an insightful essay! You bring this blogathon up to a whole new level with your wonderful academic analysis and comparison of Sontag's essay to the aesthetic created by Dietrich and Sternberg. A pleasure to read and an honor to have catalyzed!

ReplyDeleteCaroline, your kindness makes me blush! I have great respect for you because you're promoting social consciousness, which some blogathons ignore and even avoid. Movies aren't merely a means of escapism, and that's what I'm seeing during the Queer Blogathon.

DeleteJoseph,

ReplyDeleteLike Caroline, I truly enjoyed your thought provoking and insightful review as you analyze Sontag. I wasn't sure if you enjoyed Dietrich in Blonde Venus when she went all 'camp' during her gorilla dance but I adore that scene and the film from beginning to end! I can picture her in that dang blonde afro and I laugh every time.

Loved the great stills you've provided and I laughed again when you mentioned the Olsen twins and their vagabond look that is now considered chic and stylish. (I enjoy camp as long as it's not childish or degrading downright vulgar as we see in today's horrific films)

I've just started reading the other entries for the Blogathon but they'll have their work cut out for them to top the brilliant piece you have here.

Have a nice weekend!

Page

Page, I'm happy that you enjoyed this entry, and I appreciate your glowing comments! When I watch the Blonde Venus "Hot Voodoo" scene without associating any meaning to the images, I enjoy it. When I watch it with my contemporary sensibilities, I can't consider it camp and find it quite racist. The way my mind processes that scene is a bit of a twist on Sontag's note 31: "When the theme is important, and contemporary, the failure of a work of art may make us indignant. Time can change that. Time liberates the work of art from moral relevance, delivering it over to the Camp sensibility." For me, time has imbued that scene with racist overtones that people probably didn't see when they watched the movie in the '30s.

DeleteJoseph,

ReplyDeleteDietrich in Morocco would be obvious in a queer film blogatho, but you brought amazing lights to a very important part of Marlene's career. I didn't know Sontag's work before, thanks to introducing this in my life!

And, like Page, I laughed a lot with the Olsen twins caption!

Greetings,

Le

Le, I considered comparing Morocco to Katy Perry's "I Kissed A Girl" because the kissing scene comes off to me as very lezploitative (if there's no word for that in Portuguese, please be the one to coin it!). Maybe I'll do that next year.

DeleteAs for Sontag, you'll surely come across her name in film criticism, so you may grow sick of her and rue the day you ever discovered her work. For a while, that's how I felt!